The Book of Revelation has 22 chapters and presents a rich, symbolic vision that addresses suffering, worship, judgment, and the hope of a renewed creation. In this guide you will learn the chapter count, a clear chunked outline of what each section covers, the major theological themes, key symbols like seals and beasts, authorship and historical context, and practical devotional applications for modern readers. Many readers struggle to move beyond sensational headlines and want a balanced, pastoral introduction that explains how Revelation functions as both prophecy and pastoral encouragement. This article provides that balanced explanation and points toward practical study tools and communal practices that help readers apply Revelation’s lessons. We begin with a concise chapter-by-chapter orientation, then explore themes and imagery, summarize authorship and context, and conclude with concrete spiritual practices and church-level lessons tied to the seven letters. Throughout, keywords like how many chapters are in Revelation, Revelation chapters explained, and major themes of Revelation are used to help readers and search systems connect to the content.

How Many Chapters Are in the Book of Revelation?

The direct answer is simple: the Book of Revelation contains 22 chapters arranged around letters, visions, and a climactic portrayal of the new creation. This section explains the broad chapter chunks, what each group focuses on, and gives a compact table to orient readers quickly. The book moves from an epistolary opening to cycles of sevens (seals, trumpets, bowls), shifts into cosmic conflict scenes, and then brings a victorious final vision of New Jerusalem. Understanding this macro-structure helps readers track recurring motifs and prepares them to read chapter-level summaries with theological context. Below is a compact chapter-chunk table intended for quick reference and high snippet potential.

| Chapter Range | Main Events/Symbols | Short Takeaway |

|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | Letters to seven churches; Christ’s introductory titles (Rev 1) | Local pastoral exhortation and Christ’s presence among congregations |

| 4–11 | Heavenly throne, scroll and seals, first four trumpets (Rev 4–11) | God’s sovereignty and escalating divine judgment |

| 12–14 | Cosmic conflict: dragon, woman, beasts, Lamb’s victory | Spiritual conflict framed around Christ’s messianic triumph |

| 15–18 | Seven bowls, final judgments, fall of Babylon | Consummation of judgment against corrupt powers |

| 19–22 | Christ’s victory, final defeat of evil, New Jerusalem (Rev 21–22) | Restoration, worship, and the promise of a new creation |

This table gives a concise map for first-time readers and study groups. By chunking chapters, readers can approach Revelation in manageable segments and notice how themes develop across the book.

What Are the 22 Chapters of Revelation About?

The 22 chapters present a progression from address to apocalypse to new creation, with each chapter contributing specific visions, commands, or images that advance the book’s pastoral aim. Chapters 1–3 contain seven letters addressing real congregations with commendations and corrective calls to faithfulness, which frame the pastoral heart of the entire work. Chapters 4–11 shift to throne-room imagery and the opening of a sealed scroll that initiates judgments; these chapters emphasize God’s rule over history and call for worship under trial. The middle chapters, 12–14, depict cosmic conflict in symbolic narrative, showing the spiritual stakes behind earthly persecution and validating perseverance. Chapters 15–18 focus on the bowls of wrath and the fall of symbolic Babylon, warning against compromise and empire-like idolatry. The final chapters, 19–22, portray Christ’s triumphant return, the defeat of evil, and the vision of New Jerusalem where God dwells with redeemed people, offering hope and ethical orientation for faithful witness.

How Is the Book of Revelation Structured Around These Chapters?

Revelation’s structure combines epistolary elements, layered visions, and repeated cycles (notably sevens) to create a literary architecture that both reveals and conceals meaning for pastoral effect. The book opens with a salutation and seven letters that ground the visions in particular congregational circumstances, then moves into symbolic sequences—seals, trumpets, and bowls—that escalate judgment and revelation. Many scholars note chiastic and interlaced patterns; for example, interludes (like the measuring of the temple) connect cycles and maintain narrative continuity so readers can trace theological development. The use of Old Testament allusion (Daniel, Ezekiel, Psalms) serves as the interpretive key: Revelation reinterprets earlier prophetic imagery to show Christ’s sovereignty and ultimate restoration. Seeing this layered structure helps readers apply specific chapters while recognizing the book’s unified theological trajectory toward judgment, justice, and renewal.

What Are the Major Themes of the Book of Revelation?

Revelation advances a handful of interrelated themes: Christ’s triumph as the Lamb and sovereign ruler, God’s righteous judgment over evil, the call to perseverance and faithful worship, and the hope of new creation culminating in the New Jerusalem. Each theme functions both as theological claim and pastoral resource designed to encourage persecuted communities and guide ethical behavior amid pressure. The book frames cosmic events around worship scenes that repeatedly invite believers to worship the one on the throne and the Lamb, connecting doctrine to doxology. Understanding these themes helps readers move past sensationalist readings toward a devotional and theological appreciation that informs prayer, witness, and communal resilience.

| Theme | Key Verses | Practical Meaning for Today |

|---|---|---|

| Triumph of Christ | Rev 5; 19–22 | Confidence that Christ reigns despite present oppression |

| God’s Judgment | Rev 6–11; 15–16 | Trust in divine justice and call to ethical repentance |

| Perseverance & Witness | Rev 2–3; 13 | Endurance in faith, resisting compromises and false worship |

| New Creation | Rev 21–22 | Hopeful vision that shapes Christian hope and moral living |

How Does Revelation Reveal the Triumph of Jesus Christ?

Revelation portrays Jesus as the Lamb who was slain yet stands victorious, combining priestly sacrifice and kingly sovereignty in symbolic and narrative imagery. Key scenes—such as the sealed scroll’s opening where only the Lamb is worthy (Rev 5) and the triumphal parade of the Rider on a white horse (Rev 19)—emphasize that Christ’s victory is both sacrificial and decisive over evil. These images communicate that salvation is secured through the Lamb’s sacrificial action and enacted through God’s sovereign rule, giving believers reason for worship and courage under trial. Practically, this triumph invites worship practices centered on Christ’s lordship and shapes Christian witness: to live as those who embody the victory already won.

What Does Revelation Teach About God’s Judgment and Sovereignty?

Revelation frames judgment as an expression of God’s justice that ultimately restores creation rather than mere punitive destruction; judgment scenes reveal God’s control over history and moral accountability. The cycles of seals, trumpets, and bowls function as narrative mechanisms showing progressive divine action against injustice and idolatry, and they invite communities to repent and persevere. Rather than inspiring fear alone, judgment imagery in Revelation is pastoral: it reassures victims that wicked powers are ultimately constrained and judged. This framing encourages balanced readings that affirm God’s sovereignty while urging ethical urgency and compassionate witness in a world marked by abuse and corruption.

What Symbolism and Imagery Are Used in Revelation?

Revelation uses dense symbolic language—beasts, dragon, Lamb, Babylon, numbers like seven and 666—to communicate theological truths through vivid imagery tied to earlier Scripture. Symbols function as condensed theological statements: the dragon → often represents Satan; the Lamb → represents Christ’s sacrificial victory; Babylon → symbolizes corrupt imperial power and idolatry. Interpreting these symbols benefits from attention to Old Testament patterns and the book’s immediate pastoral aims rather than speculative futurism alone. The section below outlines how the major cycles and ps typically function and offers guidance for reading symbolic language with both restraint and imagination.

| Symbol (Entity) | Typical Interpretation | Scriptural References |

|---|---|---|

| Dragon | Satan or cosmic evil | Rev 12 |

| Lamb | Jesus Christ; sacrificial victory | Rev 5; 21–22 |

| Beasts | Political/imperial power or anti-God forces | Rev 13 |

| Seals/Trumpets/Bowls | Progressive judgment cycles | Rev 6–16 |

| Babylon | Corrupt, idolatrous systems | Rev 17–18 |

What Do the Seals, Trumpets, and Bowls Represent?

The seals, trumpets, and bowls are three interlocking cycles that portray escalating divine action toward judgment and restoration, each with a particular narrative emphasis. Seals introduce the unveiling of the scroll and bring a series of divine acts that reveal human conditions and call for worship; trumpets intensify calamity and function as warnings calling communities to heed God’s sovereignty; bowls represent the consummating outpouring of God’s righteous wrath against entrenched evil. Each cycle ties imagery back to Old Testament prophetic motifs, using symbolic language to translate cosmic truths into pastoral exhortation. Reading these cycles comparatively highlights the book’s theological coherence rather than treating each as an isolated event.

Who Are the Beasts, Dragon, and Other Symbolic Figures?

The dragon, beasts, and other antagonistic ps represent concentrated forms of opposition to God’s purposes and are typically read as symbols of Satanic or imperial power rather than merely literal individual monsters. The dragon in Revelation 12 functions as a cosmic antagonist who persecutes the faithful and seeks to thwart God’s plan, while beasts in Revelation 13 commonly symbolize political systems or rulers that demand allegiance and persecute faithful witness. Interpretive options include symbolic, historical, and futurist readings, but a pastoral hermeneutic focuses on how such ps call readers to resist idolatry and maintain faithfulness. This approach emphasizes practical application: these symbols identify patterns of power that threaten the church’s witness and invite steadfast worship and communal care.

Who Wrote the Book of Revelation and What Is Its Historical Context?

Traditionally, Revelation is attributed to John of Patmos, a visionary p who identifies himself in the text and communicates messages to seven churches in Asia Minor. Textual evidence and early Christian tradition link this John to a prophetic seer known as John of Patmos rather than providing decisive biographical details about his life; scholarly debate continues about his precise relationship to the apostle John. The book’s late first-century dating is widely argued because its themes and references resonate with conditions under Roman imperial pressure, particularly during the reign of Emperor Domitian (c. AD 81–96). For readers seeking deeper historical and philological study, using focused study tools can illuminate the text’s background and interpretive options.

If you want targeted historical or textual questions answered, FaithTime’s AI-powered Bible Chat provides a way to ask focused questions about authorship, dating, and ancient context. Bible Chat is designed to offer contextualized scriptural explanations alongside devotional reflection, helping readers track citations and historical connections. Using Bible Chat can help readers parse contested issues—such as the identity of John of Patmos—without losing sight of Revelation’s pastoral intent. This brief referral connects study needs with practical tools for ongoing reflection and learning.

Who Is John of Patmos and What Was His Role?

John of Patmos identifies himself within the book as a recipient of visions and as the messenger to the seven churches, functioning primarily as a visionary-author whose role is to disclose images given to him for the churches’ encouragement and warning. The text presents John as a p on an island (Patmos) where he received the revelation, emphasizing prophetic authority grounded in visionary experience rather than institutional rank. While tradition sometimes links John of Patmos to the apostle John, the text itself focuses on his role as visionary and communicator, and scholarly debate remains open on familial identity. For pastoral reading, the key point is John’s function: he serves as the prophetic mouthpiece through whom Christ addresses congregations under pressure.

What Was the Historical Setting During Roman Persecution?

Evidence suggests Revelation addresses communities experiencing imperial pressure and the cultural demands of emperor worship, which created social and spiritual tensions for early Christians. The book’s vivid imagery and polemic against “Babylon” reflect critique of imperial and economic systems that coerced allegiance, while calls to endurance and faithful testimony respond to real threats of marginalization or sanction. Apocalyptic language in this setting functions pastorally: it reframes present suffering by assuring believers that cosmic justice and divine sovereignty will prevail. Readers should approach historical claims with caution—recognizing patterns of pressure rather than assuming precise forensic detail—while allowing the book’s pastoral message to shape ethical and communal responses.

How Can Understanding Revelation’s Structure and Themes Help Today?

Understanding Revelation’s structure and themes equips modern readers to practice perseverance, prioritize worship, and sustain hope amid cultural pressures that mirror ancient challenges. The book’s vision of Christ’s triumph encourages congregations to resist compromise and to center their life together around worship and faithful witness, translating symbolic claims into ethical commitments. Practically, readers can adopt disciplined devotional habits—daily readings, reflective prayers, and community sharing—that keep Revelation’s promises and warnings present in ordinary life. Below is a brief list of practical steps readers and small groups can adopt to apply Revelation’s lessons in contemporary contexts.

- Daily Scripture Reading: Read a short Revelation passage with a reflection question to build familiarity and spiritual resilience.

- Worship-Focused Prayer: Use imagery from Revelation (throne-room language, the Lamb) to center corporate and personal worship around Christ’s sovereignty.

- Community Testimony: Share stories of faithful endurance in small groups to encourage mutual perseverance and accountability.

These practices help translate Revelation’s symbolic language into habits that sustain faith in daily life. For those seeking guided options, FaithTime’s devotional tools—devotion tracking, community prayer, and the AI-driven Bible Chat—can structure a reading plan and provide conversational study support without replacing communal discernment. FaithTime’s features are designed to make daily devotion and scriptural questions accessible, supporting the very practices that Revelation emphasizes: worship, witness, and perseverance.

What Spiritual Lessons Does Revelation Offer for Perseverance and Worship?

Revelation repeatedly models perseverance as active faithfulness under pressure and locates worship at the center of Christian identity, offering concrete spiritual lessons for communities and individuals. Letters to the seven churches emphasize endurance, repentance, and promise-based motivation, showing that perseverance involves both moral correction and sustained hope grounded in Christ’s lordship. Worship scenes (throne-room visions) teach believers to reorient affections toward God rather than transient powers, and liturgical practices drawn from these images can reinforce communal resilience. Reflective prompts—such as identifying present “Babylons” to resist or naming ways the community can practice faithful witness—help translate vision into action and prepare congregations to embody Revelation’s call to steadfast worship.

How Does Revelation Provide Hope Through the New Jerusalem and New Creation?

The vision of the New Jerusalem at the end of Revelation presents hope not as abstract optimism but as a concrete picture of restored relationship: God dwelling with people, the removal of mourning, and the healing of creation. Revelation 21–22 reframes present suffering within the telos of God’s purposes, offering ethical motivation: if the future is renewal rather than annihilation, present life is oriented toward justice, mercy, and faithful stewardship. Devotionally, meditating on New Jerusalem can cultivate patience and a longing that shapes choices—prioritizing love and integrity over immediate gain. A short prayer practice imagining the city’s features can help believers embody hope in tangible habits of care and worship.

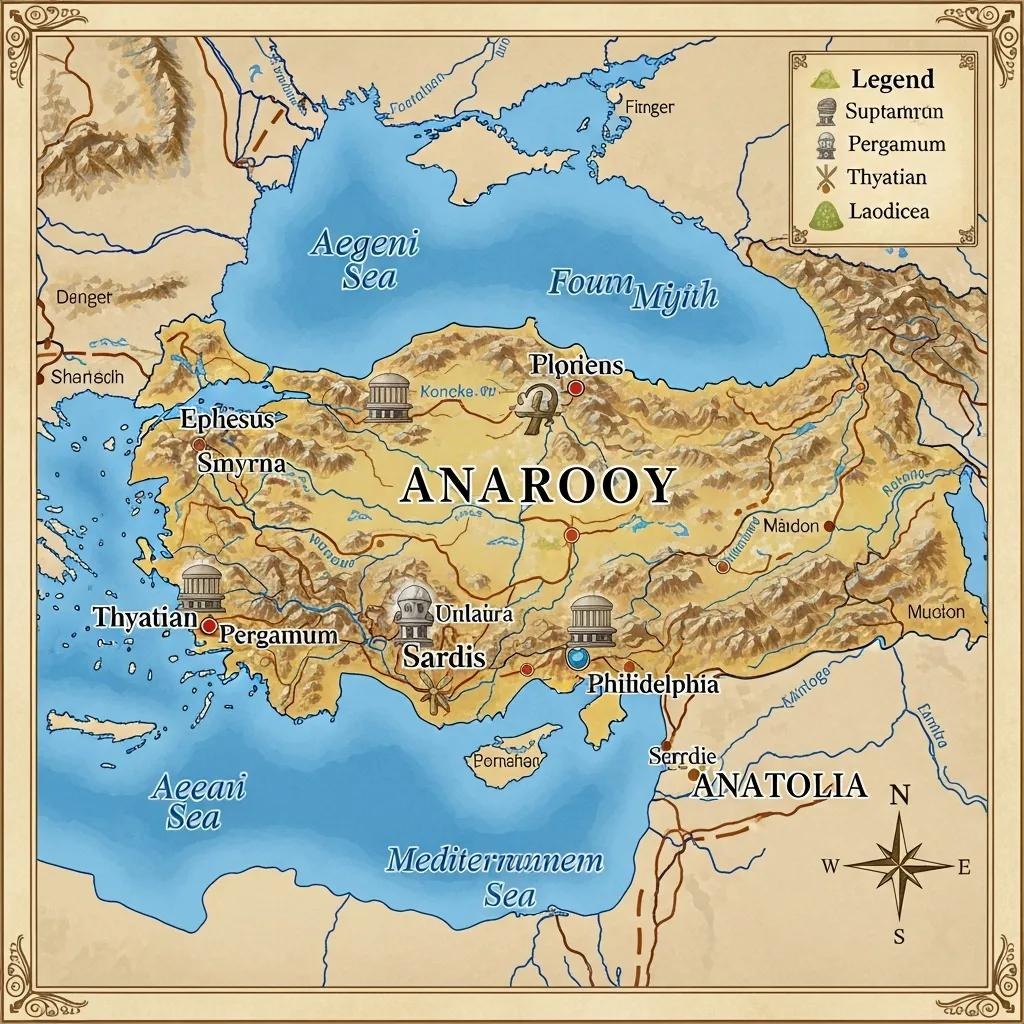

What Are the Seven Churches of Asia Minor and Their Messages in Revelation?

The seven churches—Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea—represent concrete congregations in Asia Minor and, by extension, recurring pastoral situations faced by churches in all ages. Each letter contains commendations, criticisms, and promises tailored to the congregation’s situation, offering both specific counsel and universal pastoral principles. Mapping these churches geographically and thematically helps readers see patterns: some churches need reform, others endurance, and others faithful witness despite suffering. Below is a concise list with one-line context markers and a summary of Christ’s message to each church.

- Ephesus: A major urban church commended for labor but called to recover love and first devotion.

- Smyrna: A suffering church encouraged to endure persecution and faithful witness.

- Pergamum: A church facing compromise with idolatry and pressured to repent.

- Thyatira: Noted for service but warned against tolerating corrupt teaching.

- Sardis: Criticized for spiritual deadness despite reputation; called to wake and strengthen what remains.

- Philadelphia: Praised for faithfulness, given promise of protection and open doors.

- Laodicea: Rebuked for lukewarmness and called to repent and seek earnest devotion.

These summaries help modern readers discern which pastoral posture each letter intends to cultivate: repentance, endurance, fidelity, or reform. For congregations wanting a structured study, an interactive map or week-long devotion series can walk communities through each letter, encouraging reflection and practical responses; FaithTime’s community features and devotion tracking can support such a series and provide a space for shared reflection and prayer.

Which Are the Seven Churches Addressed in Revelation?

The seven churches mentioned are Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea, each located in Asia Minor and each facing a distinct pastoral situation that yields timeless lessons. Historically, these cities were urban centers with unique social and economic configurations that influenced the churches’ challenges, such as trade networks or local cultic practices. The letters combine commendation with corrective counsel, shaping a template for congregational health across eras. Studying them in sequence reveals recurring themes—faithfulness, repentance, endurance—that remain relevant for present-day church life.

What Are the Key Messages Jesus Christ Sends to These Churches?

Across the seven letters, key messages cluster around calls to repentance, steadfast endurance, guarding doctrinal and moral purity, and the promise of reward for faithfulness; Christ’s messages are both particular and paradigmatic. Promises—such as access to the tree of life or being made a pillar in God’s temple—function as motivational imagery that ties ethical demands to eschatological hope. For modern churches, these letters invite practices of accountability, communal confession, and renewed devotion that resist cultural assimilation. Practical steps include local congregational audits of worship priorities, intentional discipleship practices, and communal prayer rhythms that reinforce the commitments urged in the letters.

The Book of Revelation → contains → 22 chapters. The book’s structure and images are designed to strengthen worship, deepen perseverance, and orient communities toward the hope of the New Jerusalem. FaithTime’s study tools—devotion tracking, a supportive prayer community, and the AI-powered Bible Chat—offer practical aids for readers who want guided, interactive study and daily application as they engage this rich biblical book.

For readers who want ongoing tools to explore Revelation and other parts of Scripture, you can also visit the main FaithTime platform to discover Bible study resources, prayer helps, and devotional guides. If you would like to keep growing in how you read Scripture as a whole, consider exploring FaithTime’s curated Bible lessons for spiritual growth, which offer short, structured studies that complement a careful reading of Revelation. Because Revelation is filled with passages about endurance, worship, and hope, you may also benefit from browsing Bible verses by topic to find passages on perseverance, God’s justice, and new creation that can anchor your study in prayer.

If the letters to the seven churches and Revelation’s repeated calls to endurance stood out to you, take time to reflect on a focused list of Bible verses about perseverance, which gathers passages that encourage steadfast faith in seasons of pressure. To deepen the worship themes highlighted in Revelation’s throne-room scenes, you can meditate on Bible verses about worship that celebrate God’s holiness and help shape personal and corporate praise around Christ’s sovereignty.